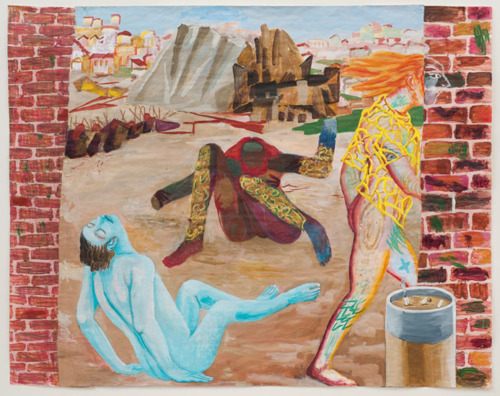

Charles Garabedian, now 87 and an elder statesman of narrative painting, embarked on a Homeric/Freudian journey half a century ago. In the 1960’s milieu of California Finish/Fetish and Light-and Space sculpture he turned to themes from Greek poetry and nineteenth century opera as paths to investigate the dimensions of his own psyche. He formulated his challenge as a figure/landscape problem and his paintings of subjects, mostly nude, sometimes halfed, beheaded or otherwise grandly burdened, wrestle mythic imagery until something resembling conclusion begins to take place. Garabedian initiates dialog with archetypes like Achilles, Prometheus, Tannhauser, Ulysses, Venus, Sekhmet, and Salome rather than costumed stand-ins assuming heroic poses. Underlining the enterprise is a feeling for time that spreads as fluidly as Pacific light, tempting the viewer to sign on the journey. We are never distant from myth, and many of Garabedian’s Santa Monica colleagues had studios on the grounds of the closed-down nautical themed Pacific Ocean Park.

The “present” is the enemy of Time. Matisse thwarted Joyce’s wish to have his novel Ulysses illustrated with scenes of Dublin c.1904. The painter instead produced archaic imagery from Homer’s tale. “Contemporary” is the shortest way around the problem of time. Bergson’s “duree” is an insufficient dimension. Joyce’s “time” is his own, as is Matisse’s, as is Garabedian’s. His psyche wanders in deserts inhabited by saints and titans. Light and architecture tie the works together, along with a sensational and endlessly evolving tale. Luminous acrylic atmosphere, through which traces of beginnings and changes emerge, stresses the paper, sliced from an appropriately immense roll the artist bought years ago and which continues to supply him with narrative pictorial surface. At various times Rivera, Gaugin, Savinio, Piero, Bellini, and Guston have been on board, as well as Wagner: artists engaged in life’s matters of talking, eating, sleeping, building, murdering and singing.

Garabedian’s elastic imagination is perfectly suited to his subject matter. He will employ a fifty foot canvas if the conversation requires generous space. He subverts the tradition of the “grand narrative” for his personal journey, whether through visions of wasted Troy or whimsical Venusberg. We know we have reached the farthest end of the world when we find Prometheus chained to Zeus’ rock. Painting never had a muse, perhaps for good reasons. Complete freedom might be one, and the remote possibility that painting can make the world a better place: substantially the same, but a bit more epic.

Jim Long 2012

(photos: Procropolis, Hector, and Achilles, 2011, acrylic on paper, 47 ¾ x 60 ½ in. (121.3 x 153.7 cm), Installation photography, Charles Garabedian: Mythologies, Betty Cuningham Gallery)

See more on Charles Garabedian: Mythologies at Betty Cuningham Gallery